Applying word2vec to Recommenders and Advertising

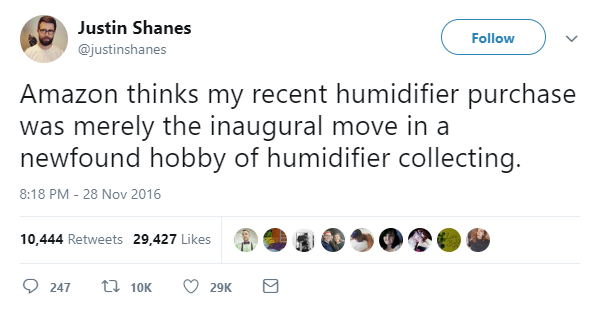

In this article, I wanted to share about a trend that’s occurred over the past few years of using the word2vec model on not just natural language tasks, but on recommender systems as well.

The key principle behind word2vec is the notion that the meaning of a word can be inferred from it’s context–what words tend to be around it. To abstract that a bit, text is really just a sequence of words, and the meaning of a word can be extracted from what words tend to be just before and just after it in the sequence.

What researchers and companies are finding is that the time series of online user activity offers the same opportunity for inferring meaning from context. That is, as a user browses around and interacts with different content, the abstract qualities of a piece of content can be inferred from what content the user interacts with before and after. This allows ML teams to apply word vector models to learn good vector representations for products, content, and ads.

“Researchers from the Web Search, E-commerce and Marketplace domains have realized that just like one can train word embeddings by treating a sequence of words in a sentence as context, the same can be done for training embeddings of user actions by treating sequence of user actions as context.” - Mihajlo Grbovic, Airbnb

So What?

word2vec (and other word vector models) have revolutionized Natural Language Processing by providing much better vector representations for words than past approaches. In the same way that word embeddings revolutionized NLP, item embeddings are revolutionizing recommendations.

User activity around an item encodes many abstract qualities of that item which are difficult to capture by more direct means. For instance, how do you encode qualities like “architecture, style and feel” of an Airbnb listing?

The word2vec approach has proven successful in extracting these hidden insights, and being able to compare, search, and categorize items on these abstract dimensions opens up a lot of opportunities for smarter, better recommendations. Commercially, Yahoo saw a 9% lift in CTR when applying this technique to their advertisements, and AirBNB saw a 21% lift in CTR on their Similar Listing carousel, a product that drives 99% of bookings along with search ranking.

![The Inner Workings of word2vec][inner_workings_ad]

Four Production Examples

Every e-commerce, social media, or content sharing site has this kind of user activity, so this approach appears to have very wide applicability. In the following sections I’ll summarize four publicized use cases of this technique which have been put into production:

- Music recommendations at Spotify and Anghami

- Listing recommendations at Airbnb

- Product recommendations in Yahoo Mail

- Matching advertisements to search queries on Yahoo Search.

Music Recommendations

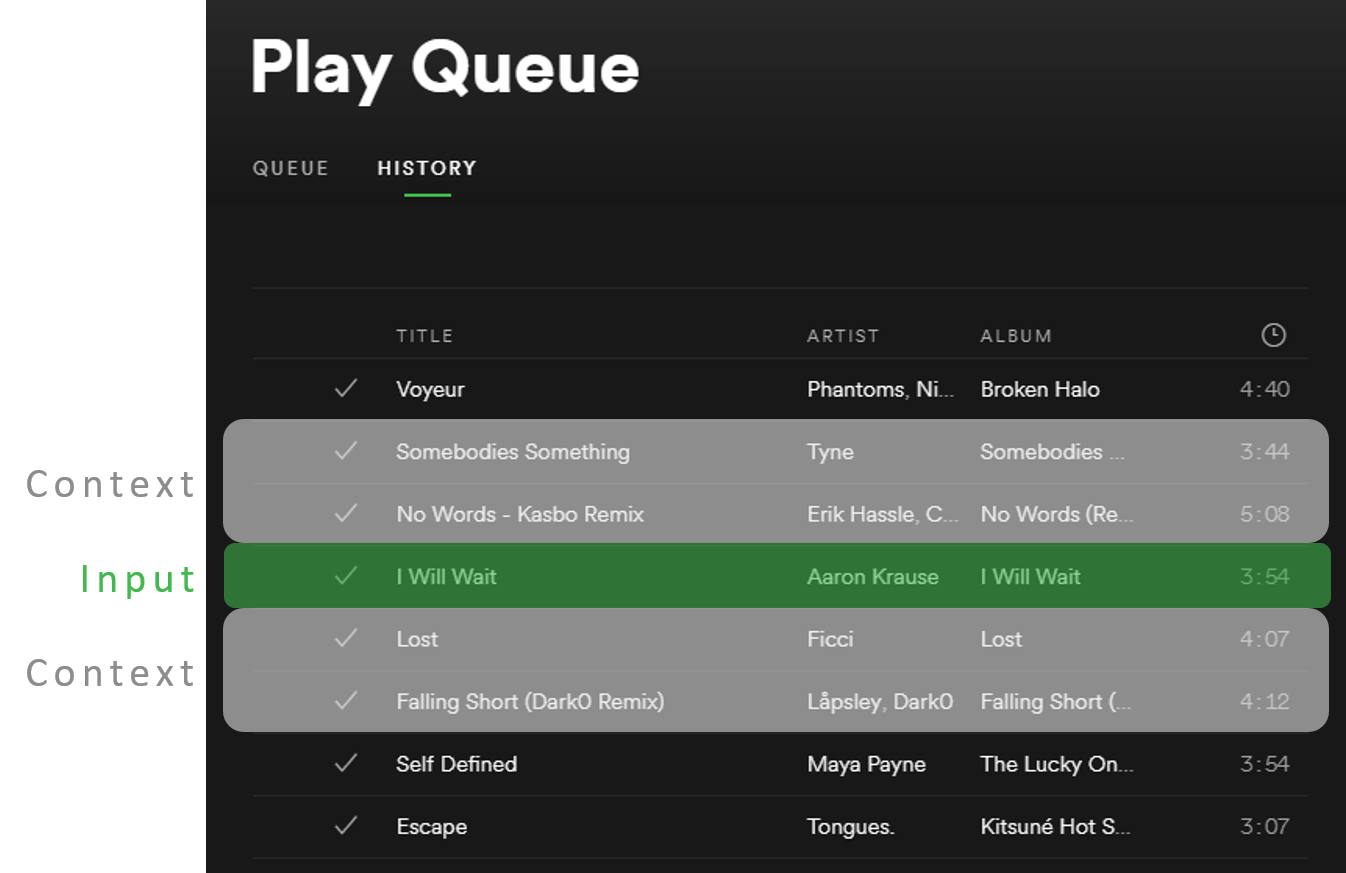

Erik Bernhardsson, who developed the approximate nearest neighbors library “Annoy” while at Spotify, has mentioned (in a meet up talk here and in a blog post here) that Spotify experimented with this technique while he was there. The most informative discussion I’ve read of this technique, however, comes from Ramzi Karam at Anghami, a popular music streaming service in the Middle East.

In his well illustrated article, Ramzi explains how a user’s listening queue can be used to learn song vectors in the same way that a string of words in text is used to learn word vectors. The assumption is that users will tend to listen to similar tracks in sequence.

Ramzi says Anghami streams over 700 million songs a month. Each song listen is like a single word in a text dataset, so Anghami’s listening data is comparable in scale to the billion-word Google News dataset that Google used to train their published word2vec model.

Ramzi also shares some helpful insights into how these song vectors are then used. One use is to create a kind of “music taste” vector for a user by averaging together the vectors for songs that a user likes to listen to. This taste vector can then become the query for a similarity search to find songs which are similar to the user’s taste vector. The article includes a nice animation to illustrate how this works.

Listing Recommendations at Airbnb

Another highly informative article on this subject comes from Mihajlo Grbovic at Airbnb.

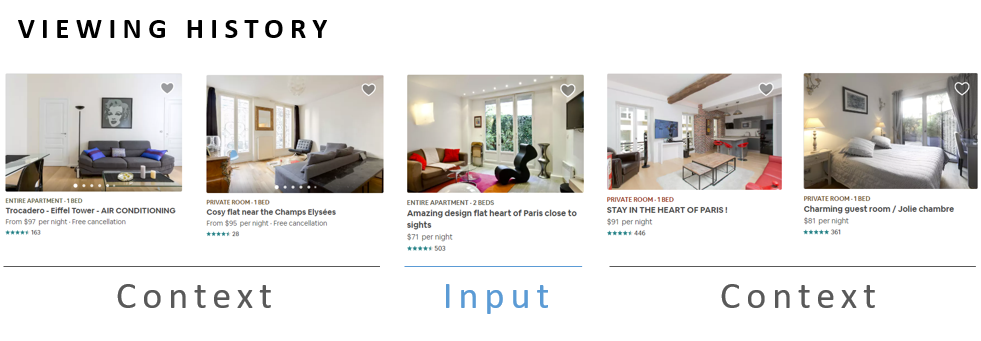

Imagine you are looking for an apartment to rent for your vacation to Paris. As you browse through the available homes, it’s likely that you will investigate a number of listings which fit your preferences and are comparable in features like amenities and design taste.

Here the user activity data takes the form of click data, specifically the sequence of listings that a user viewed. Airbnb is able to learn vector representations of their listings by applying the word2vec approach to this data.

Airbnb made a few interesting adaptations to the general approach in order to apply it to their site.

An important piece of the word2vec training algorithm is that for each word that we train on, we select a random handful of words (which are not in the context of that word) to use as negative samples. Airbnb found that in order to learn vectors which could distinguish listings within Paris (and not just distinguish Paris listings from New York listings), it was important that the negative samples be drawn from within Paris.

Grbovic also explains their solution to the cold start problem (how to learn vectors for new listings for which there isn’t user activity data)–they simply averaged the vectors of the geographically closest three listings to the new listing to create an initial vector.

These listing vectors are used to identify homes to show in the “similar listings” panel on their site, which Grbovic says is an important driver of bookings on their site.

This was not the first time Grbovic has applied the word2vec model to recommendations–he worked on the next two examples as well while at Yahoo Labs.

Product Recommendations in Yahoo Mail

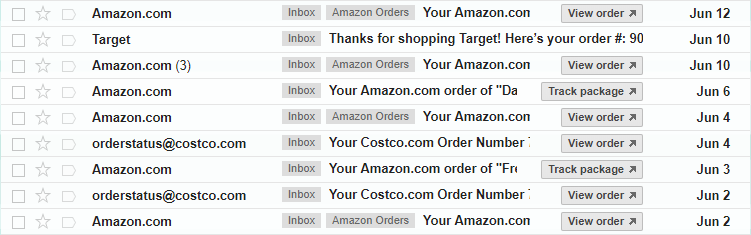

Yahoo published a research paper detailing how they use purchase receipts in a user’s email inbox to form a purchase activity, allowing them in turn to learn product feature vectors which can be used to make product recommendations. Like the other applications presented here, it’s worth noting that this approach has gone into an actual production system.

Since online shoppers receive e-mail receipts for their purchases, mail clients are in a unique position to see user purchasing activity across many different e-commerce sites. Even without this advantage, though, Yahoo’s approach seems applicable and potentially valuable to online retailers as well.

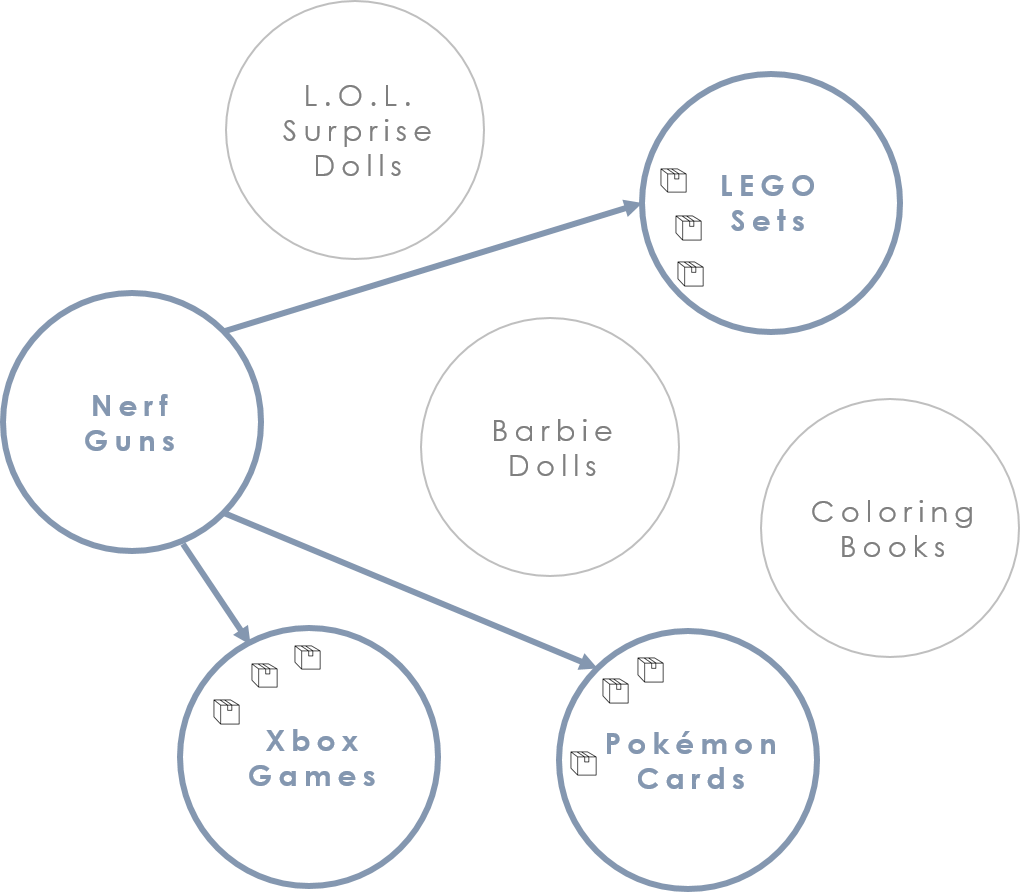

Here, the user activity is their sequence of product purchases extracted from the e-mail receipts. The word2vec approach is able to learn embeddings for the products based on the assumption that shoppers often buy related items in sequence. For instance, perhaps they are purchasing a number of items around the same time because they go together (like a camera and a lens), or because they are all part of a project they are working on, or because they are preparing for a trip they are taking. A user’s sequence of purchases may also reflect shopper taste–shoppers who like item A also tend to like item B and are interested in buying both.

This may seem a little strange given that the products we purchase aren’t always related. But remember that the model is governed by the statistics of user behavior–if two products are related, they are going to be purchased together by many users (thereby occurring together more in the training data, and having more influence on the model), while any two unrelated products will be purchased together much less often and have little influence on the model.

Yahoo augmented the word2vec approach with a few notable innovations. The most interesting to me was their use of clustering to promote diversity in their recommendations. After learning vectors for all the products in their database, they clustered these vectors into groups. When making recommendations for a user based on a product the user just purchased, they don’t recommend products from within the same cluster. Instead, they identify which other clusters users most often purchase from after purchasing from the current cluster, and they recommend products from those other clusters instead.

I imagine this clustering technique helps eliminate the problem of recommending the equivalent of product “synonyms”. That is, imagine if the system only ever recommended different versions of the same item you just bought–“You just bought Energizer AA batteries? Check out these Duracell AA batteries!” Not very helpful.

To choose specific products in those clusters to recommend, in each cluster they find the ‘k’ most similar products to the purchased product, and recommend all of these to the user. In their experiments, they identified 20 products to recommend to the user per day. Each time a user interacts with the Yahoo Mail client, the client displays another one of the product recommendations in the form of another ad.

The paper also describes a technique called “bagging” where they assign additional weight to products which appear on the same purchase receipt.

Matching Ads to Search Queries

In this application (published here), the goal is to learn vector representations for search queries and for advertisements in the same “embedding space”, so that a given search query can be matched against available advertisements in order to find the most relevant ads to show the user.

This is a particularly fascinating application given the number of daunting challenges this problem poses (and yet they solved them and put this into production!). How do you learn vectors for queries and ads at the same time? How could you possibly learn a vector for search queries given the seemingly infinite number of possible queries out there? And how do you apply this when new queries and new ads are appearing daily?

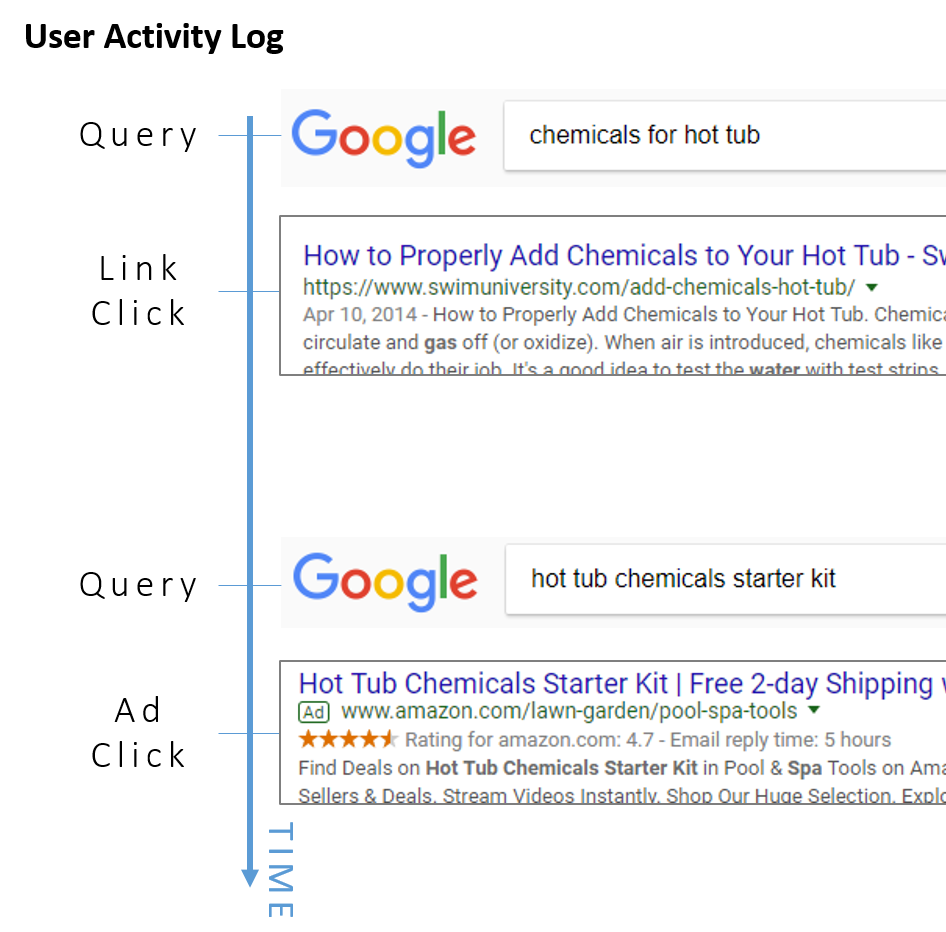

The solution to learning vectors for queries and ads at the same time is fairly straightforward. The training data consists of user “search sessions” which consist of search queries entered, advertisements clicked, and search result links clicked. The sequence of these user actions is treated like the words in a sentence, and vectors are learned for each of them based on their context–the actions that tend to occur around them. If users often click a particular ad after entering a particular query, then we’ll learn similar vectors for the ad and the query. All three types of actions (searches entered, ads clicked, links clicked) are part of a single “vocabulary” for the model, such that the model doesn’t really distinguish these from one another.

Even though this application is focused on matching search queries and advertisements, the addition of the link clicks provides additional context to inform the other embeddings. (Though it’s not the subject of their research paper, you have to wonder whether they might use these link embeddings to help in ranking search results…)

What about the scale of this problem? Surely there are too many unique queries, links, and ads for this to be feasible? This is at least partially addressed by only keeping items in the vocabulary which occur more than 10 times in the training data; they imply that this filters out a large portion of unique searches. Still, the remaining vocabulary is massive–their training set consisted of “126.2 million unique queries, 42.9 million unique ads, and 131.7 million unique links”, a total of 300.8 million items.

They point out that, for 300-dimensional embeddings, a vocabulary of 200 million items would require 480GB of RAM, so training this model on a single server is out of the question. Instead, they detail a distributed approach that made this training feasible.

So they’ve tackled the scale problem, but what about the severe cold start problem caused by the daily addition of new search queries and ads? I found the details of their methods here difficult to follow, but the general strategy appears to be matching words in the new material to words in old material, and leveraging those existing embeddings to create an initial embedding for the new content.

This method was placed into production, but apparently not all advertisements are chosen this way–they say that their approach is “currently serving more than 30% of all broad matches”, where “broad matches” refers to attempts to match queries to ads based on the intent of the queries rather than on simple keyword matching.

Similarity Search

This approach of learning content vectors based on user activity data is an exciting development for Nearist, since the most common operation with these vectors is to perform a similarity search to make content recommendations.

Given the large amount of vectorized content and the large number of users for which recommendations need to be made, this similarity search becomes a challenging engineering problem. Companies like Spotify and Facebook have invested a great deal of effort into developing approximation techniques to make this search feasible at scale, but with a cost to accuracy and clearly a large cost in engineering effort. And when the quality of product recommendations directly affects revenue, accuracy matters!

At Nearist, we believe the efforts of machine learning teams are better spent on improving the quality of your vector representations than on solving similarity search at scale, and we’ve made it our goal to provide as much search capability as you need with minimal engineering effort. Learn more at Nearist.ai.