GLUE Explained: Understanding BERT Through Benchmarks

By Chris McCormick and Nick Ryan

In this post we take a look at an important NLP benchmark used to evaluate BERT and other transfer learning models!

Introduction

The General Language Understanding Evaluation benchmark (GLUE) is a collection of datasets used for training, evaluating, and analyzing NLP models relative to one another, with the goal of driving “research in the development of general and robust natural language understanding systems.” The collection consists of nine “difficult and diverse” task datasets designed to test a model’s language understanding, and is crucial to understanding how transfer learning models like BERT are evaluated.

What is a NLP task and what is its relevance to my work?

NLP tasks all seek to test a model’s understanding of a specific aspect of language. For:

- Named Entity Recognition: which words in a sentence are a proper name, organization name, or entity?

- Textual Entailment: given two sentences, does the first sentence entail or contradict the second sentence?

- Coreference Resolution: given a pronoun like “it” in a sentence that discusses multiple objects, which object does “it” refer to?

In all likelihood, you’re much more interested in your own fun/profitable task like using BERT to predict the sentiment of customer reviews, so coreference resolution benchmarking isn’t obviously a thing that should interest you. However, it’s helpful to understand that all of these discrete tasks, including your own application and a coreference resolution task, are connected aspects of language. So while you may not be interested in coreference resolution or textual entailment, when it comes time to evaluate the sentiment of your customer reviews, a model that can be used to effectively determine things like which object “it” refers to will in the aggregate likely make your model more effective when it comes time to evaluate that ambiguously worded customer review. For that reason, when a model like BERT is shown to be effective at understanding and predicting a broad range of these canonical and fine-grained linguistic tasks, it’s an indication that the model will probably be effective for your application.

Why was GLUE created?

In the past, NLP models were nearly always designed around performing well on a single, specific task. The best performing models had specialized architectures (often a very specific type of LSTM) designed with this one task in mind, were trained end-to-end on this task, and rarely had the same level of success generalizing to other tasks or datasets.

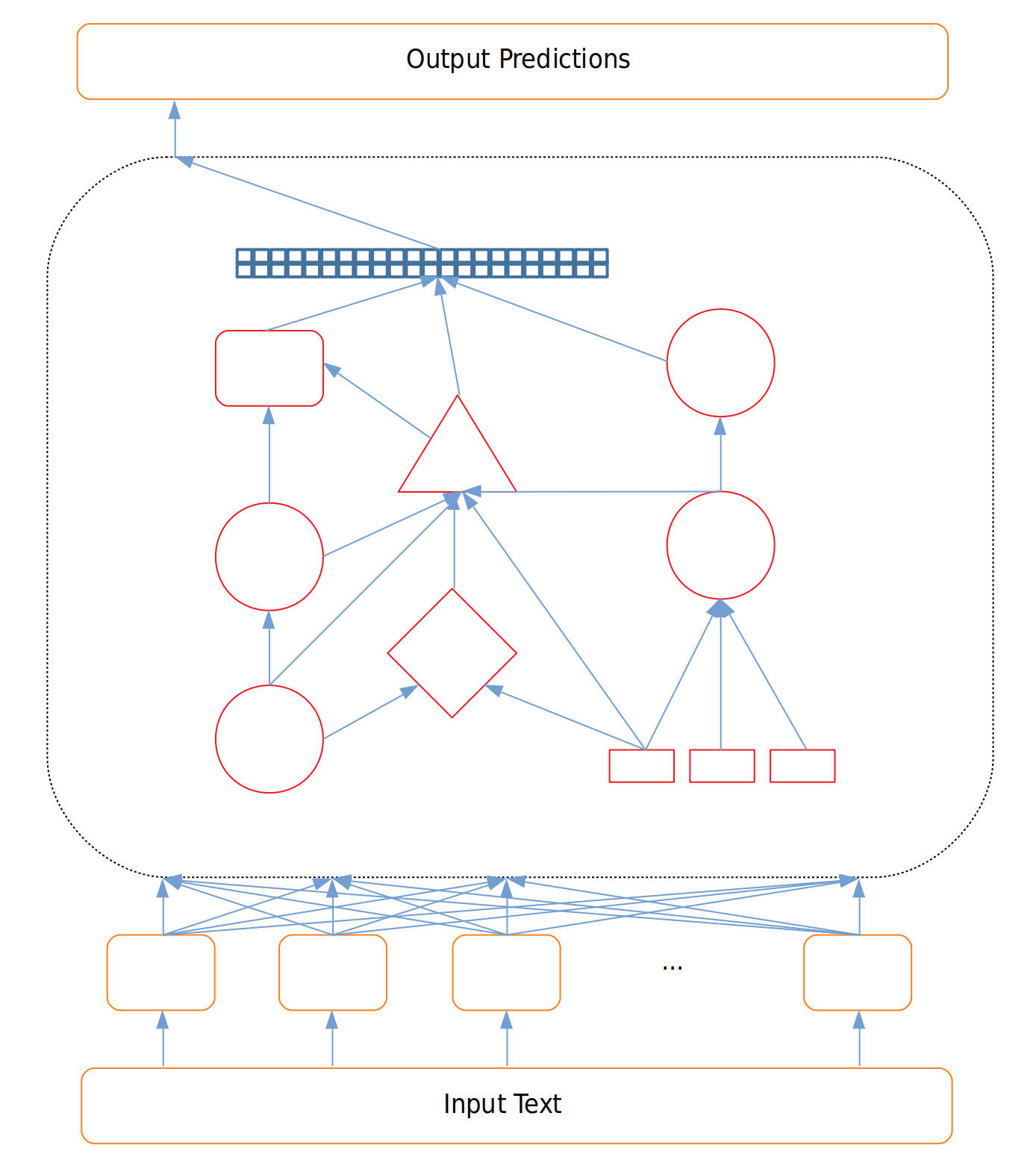

Figure 1: Highly Specialized Architecture

Because these models are designed with a specific task or even a specific dataset in mind, evaluating the model was as simple as evaluating it on the task it was trained for. Is the NER model good at NER?

However, as people began experimenting with transfer learning and the success of transfer learning in NLP took off, a new method of evaluation was needed.

Unlike single task models that are designed for and trained end-to-end on a specific task, transfer learning models extensively train their large network on a generalized language understanding task. The idea is that with some extensive generalized pretraining the model gains a good “understanding” of language in general. Then, this generalized “understanding” gives us an advantage when it comes time to adjust our model to tackle a specific task. By:

- Removing the input and output layers we used for generalized pretraining

- Replacing them with the task-specific input/output layers we’re interested in

- Continuing to train this new network for a few epochs we leverage the “middle” part of the model that “understands” language to help give us a leg up on our specific task.

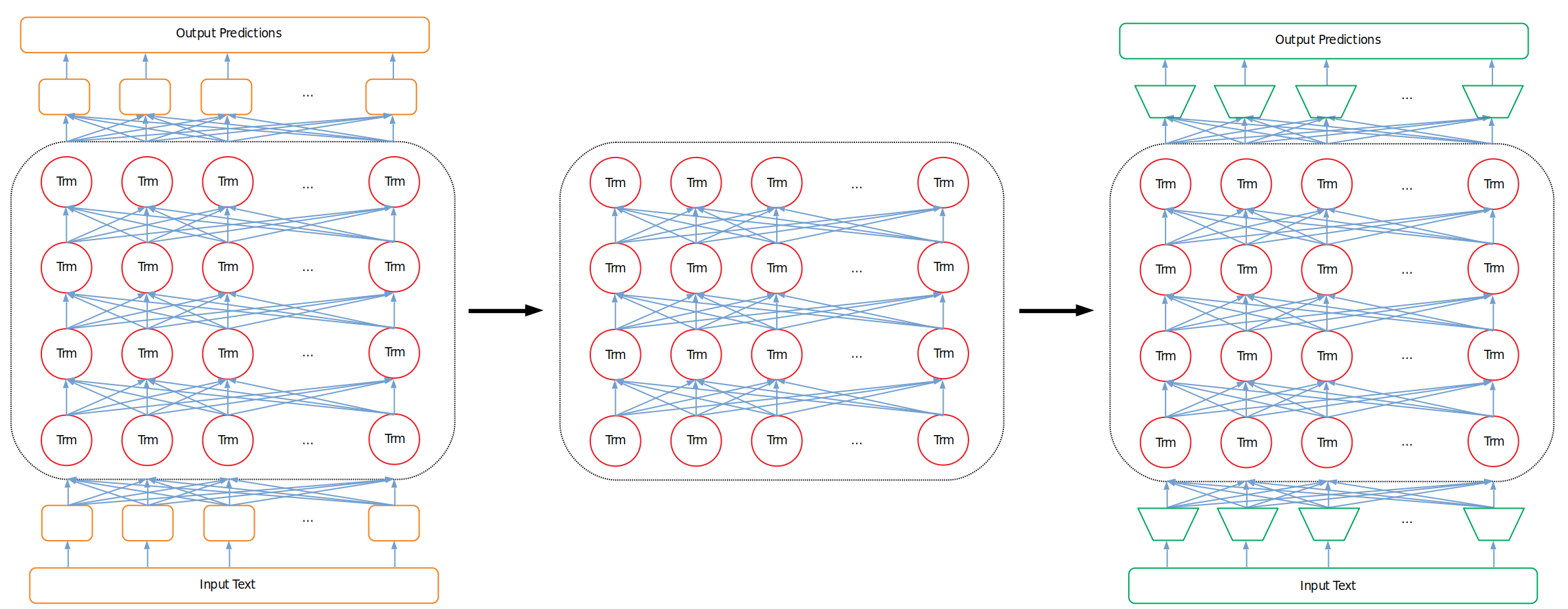

Figure 2: Initial Pretraining Architecture (Untrained), Trained Language Network, Fine-Tuning Architecture

This is the key idea behind transfer learning. As new transfer learning models emerge with different pretraining methods, an important question emerges: how do researchers evaluate the quality of these transfer learning models against one another? No single task provides a great way to do this because we want to test the general language “understanding” of these models, and get an indication of how well the model will then perform on our specific fine-tuned language task.

Creation and use of GLUE

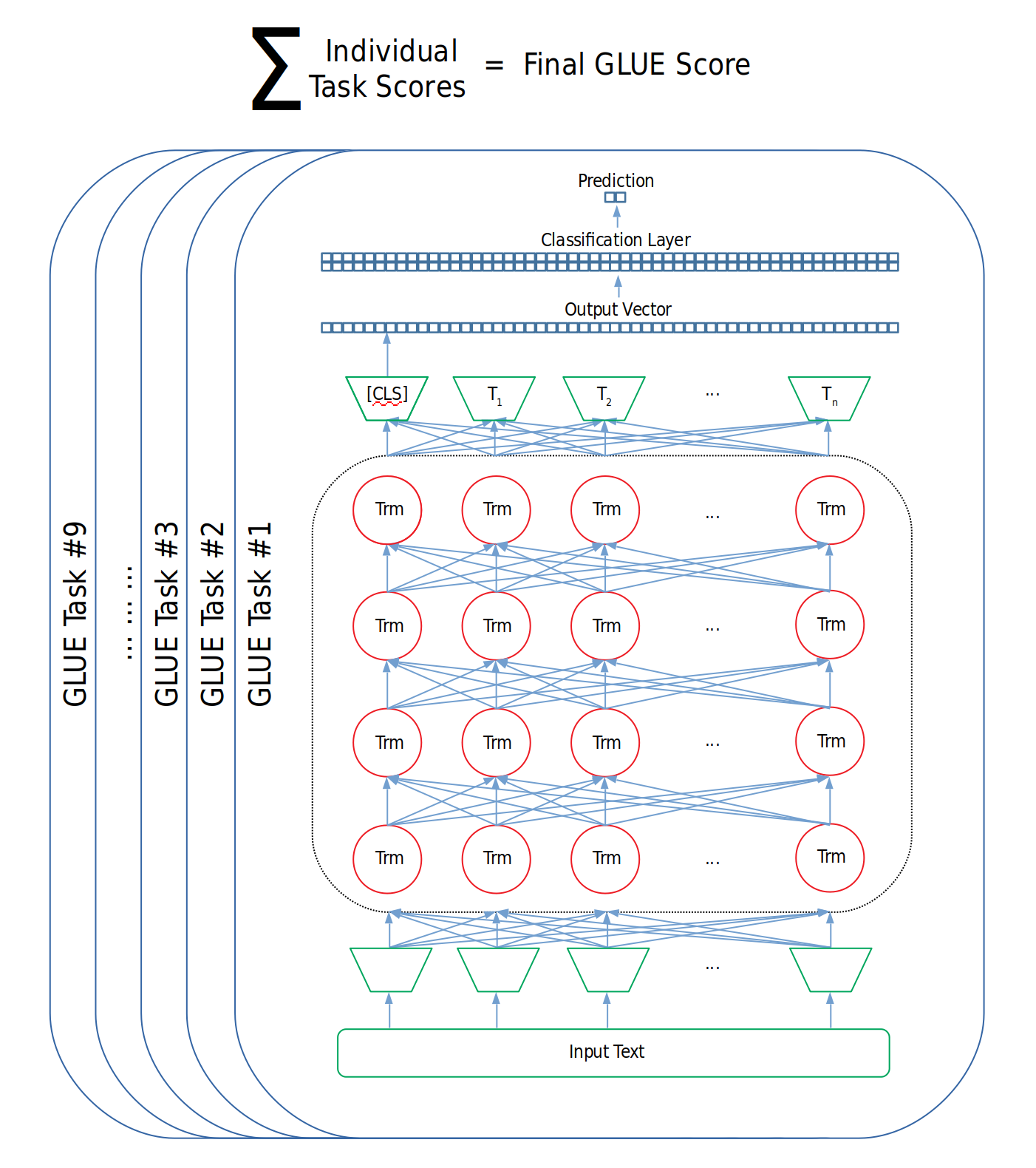

So, a team at NYU put together a collection of tasks called GLUE. When researchers want to evaluate their model, they train and then score the model on all nine tasks, and the resulting average score of those nine tasks is the model’s final performance score. It doesn’t matter exactly what the model looks like or how it works so long as it can process inputs and output predictions on all of the tasks.

Figure 3: Calculation of GLUE Score

Since its introduction, GLUE has seen wide adoption and the majority of new transfer learning models publish their results on the GLUE benchmark. This lets researchers and the broader community heuristically compare, in a single number, models against one another.

What are the tasks?

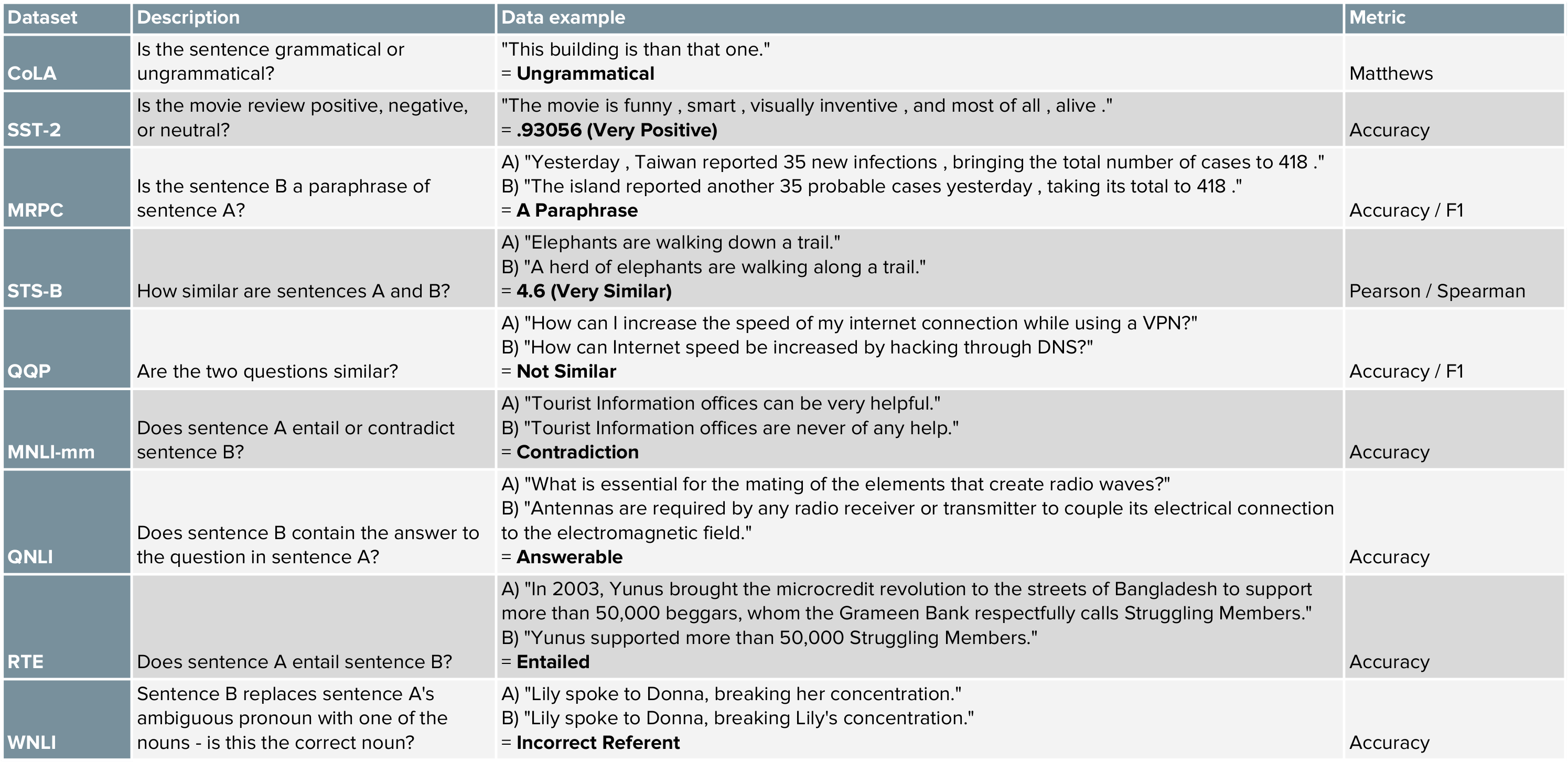

The tasks are meant to cover a diverse and difficult range of NLP problems, and are mostly adopted from existing datasets. The table below provides a handy reference for what these tasks are, and this link provides a more detailed overview.

Figure 4: Summary of GLUE Tasks

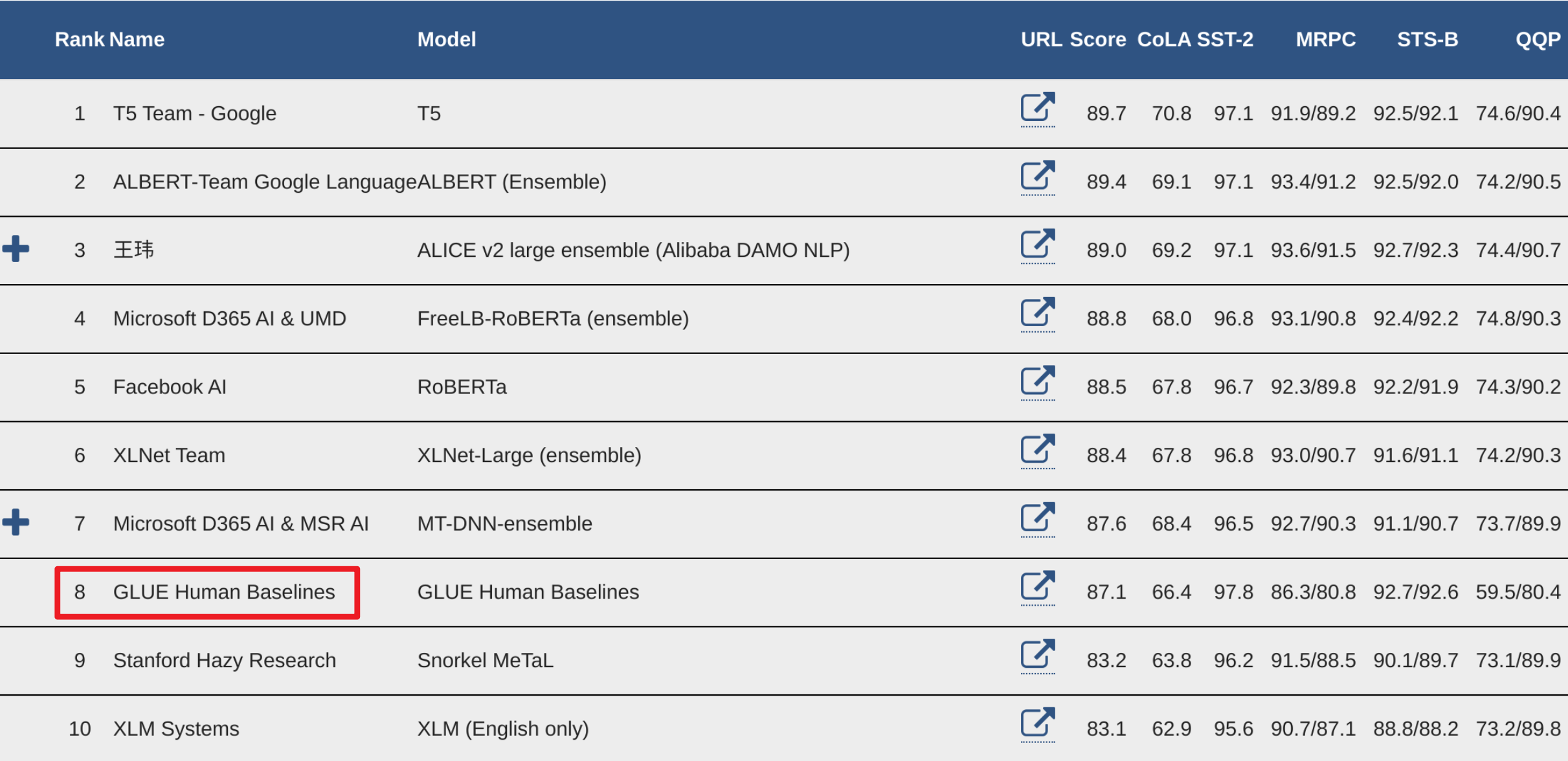

How well are these models doing when compared to humans?

GLUE includes a human benchmark in the leaderboard that has already been surpassed by a number of models. The human benchmark is a result of real people manually read through and making predictions for all of the test datasets. While some models outperform the human benchmark in the aggregate, there are specific tasks that humans regularly outperform/underperform on relative to machines.

Figure 5: GLUE Leaderboard with Human Performance Highlighted

You might be confused as to how one of these models could outperform a human. After all, if one set of humans created the true labels then shouldn’t another set of humans produce the same labels, resulting in a perfect score? However, human performance varies widely (what was your SAT score over multiple tests? against your peers?) on tasks like reading comprehension, grammatical acceptability, and determining the similarity of two things. Testing yourself on some of the datasets might help reinforce this. Even disregarding unintentional errors or fatigue (imagine labeling hundreds of these in a sitting) some of the examples are undoubtedly ambiguous.

The Winograd task (WNLI) is a good example of humans outperforming machines. This is intentional, as the task requires common sense and practical application to answer correctly, and is sometimes worded to intentionally foil an approach that would depend entirely on statistical co-occurence.

Where can I access the GLUE data?

This script contains instructions and code for downloading GLUE data.

This notebook shows you how to explore and selectively download datasets using tensorflow datasets (tfds).

How are models tested on GLUE?

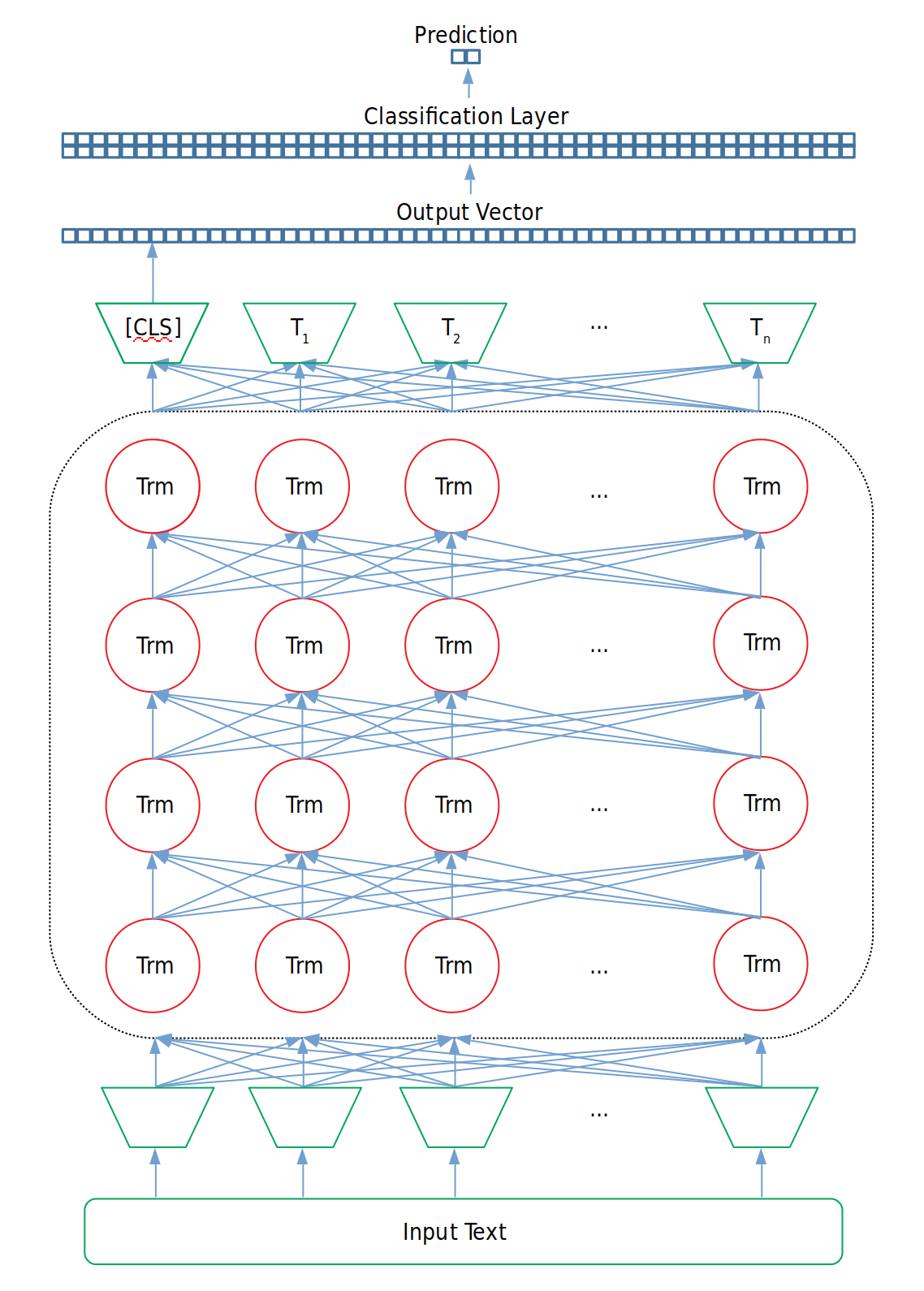

For each task, the model needs to have its input and output representation changed to accommodate the task. For example, while pretraining BERT is given two sentences with a few of the words masked (replaced with a generic [MASK] token) as input. The data flows through the main body of BERT and then goes to a classification layer that outputs both a binary decision about whether the sentences follow one another as well as predictions about what the [MASK] words actually are.

Luckily, BERT’s input representation layer doesn’t need to change because the two sentence input structure (the second sentence is actually optional) accommodates all of the GLUE tasks: the first and second sentence can be replaced with two questions for QQP, one single sentence for CoLA, a question and a paragraph for QNLI, etc.

However we do need to remove the pretraining classification layer and replace it with one that accommodates the output of each GLUE task, which is typically creating a binary prediction. For example, if our task is to create a binary prediction on small BERT (hidden layer size 768), then the classification layer will be of size [number_of_labels, hidden_layer_size], or [2, 768] that takes as input the BERT output of the [CLS] token, used as an aggregate output representation of the sentence for classification tasks. We then fine-tune the model with standard classification loss.

Figure 6: Fine-Tuning Architecture for GLUE Task Training and Evaluation

With the pytorch-transformers library from huggingface, it looks something like this:

# Outputs of BERT, corresponding to one output vector of size 768 for each input token

outputs = model(input_ids,

attention_mask=attention_mask,

token_type_ids=token_type_ids,

position_ids=position_ids,

head_mask=head_mask)

# Grab the [CLS] token, used as an aggregate output representation for classification tasks

pooled_output = outputs[1]

# Create dropout (for training)

dropout = nn.Dropout(hidden_dropout_prob)

# Apply dropout between the output of the BERT transformers and our final classification layer

pooled_output = dropout(pooled_output)

# Create our classification layer

classifier = nn.Linear(hidden_size, num_labels)

# Feed the pooled output through the classifier

logits = classifier(pooled_output)

Which is exactly what the implementation of BertForSequenceClassification looks like.

##